‘We’ve Got Wings’: IAS Officer Rescues Hundreds From Bonded Labour, Makes Them Kiln Owners

IAS officer Alby John Verghese has rescued and rehabilitated hundreds trapped in bonded labor in rural Tamil Nadu. This has led to numerous transformations in their lives.

Born in rural Tamil Nadu, Chinnathambi spent his entire childhood around as a bonded labourer at a brick kiln. This had been his life since the age of 5, and he worked into the wee hours of the day, or under the scorching sun, for as little as Rs 500 — the collective weekly income of the family of three.

His parents, he recalls, had taken a loan of Rs 10,000 from a brick kiln owner in the Tiruttani block of Tiruvallur district. “We would get Rs 250 for 1,000 bricks we made. But no matter how much work we did, we were unable to pay that loan. The owner kept us engaged and never let us free.”

After working tirelessly for 16 hours, the family would survive on bland rice and dal (pulse). Sometimes, in the absence of the owner, he would escape to school. “But whenever he would find out, he would beat me up,” he adds.

Things continued this way for about 10 years, until 2018, when he was rescued by the district administration. The life he led prior to his rescue has faded into the distance somewhere — Chinnathambi, now 33, has completed his bachelor’s degree in Arts and is living a life of dignity. Today, he co-owns a community-run brick kiln himself, where everyone works on their own terms. “It’s a wonderful feeling,” he notes.

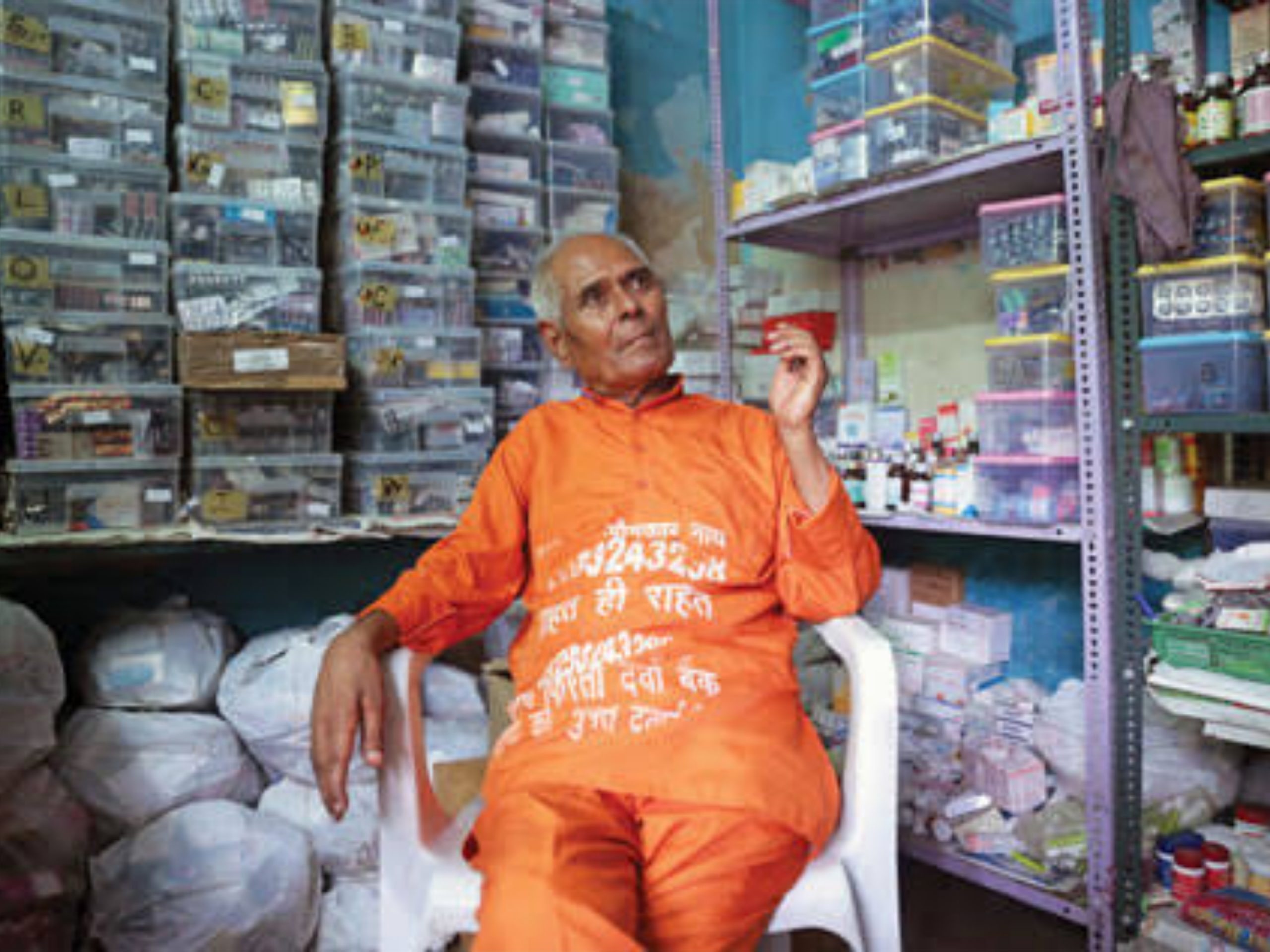

Chinnathambi is among the several workers rescued from bonded labour, thanks to the efforts of district collector Alby John Verghese. In 2022, the 34-year-old launched a unique initiative under the Tamil Nadu State Rural Livelihood Mission to turn formerly enslaved and bonded labourers into brick kiln owners.

Giving ‘wings’ to 400 bonded labourers

In India, the Bonded Labour System Act 1976 mandates the abolishing of the bonded labour system and calls for the freedom of all bonded labourers, as well as cancelling their debts, rehabilitating the victim, and punishing the offender. Despite being outlawed nearly five decades ago, the practice remains — thousands of labourers are trapped in the cycle of slavery in the country’s brick kilns, rice mills, textile companies, and factories.

As per the 2018 data by the Union Ministry of Labour & Empowerment, as many as 313,687 bonded labourers were identified in the country. Of this, 65,573 were identified in Tamil Nadu – the second highest after Karnataka.

Meanwhile, the Tiruvallur district has rescued more than 400 former bonded labourers in the district since 2017. However, after getting rescued, it was not easy for these workers to find livelihood options. So last April, a group of these villagers, including Chinnathambi, went to the collector to seek help.

In conversation with The Better India, Verghese notes, “They informed that even after the rescue, it was very difficult for erstwhile bonded labourers to find jobs. We started working with multiple stakeholders including communities and brick kiln associations to come up with solutions.”

In 2022, Verghese inaugurated Siragugal Bricks — a community-owned brick kiln for rescued bonded labourers. In English, Siragugal means ‘wings’, which is telling of the present status of these workers — the initiative has given “wings” to about 400 people in the district.

“Today, we earn Rs 1,000 for the 1,000 bricks we make and in a week, I am able to earn up to Rs 4,500. We have set up working hours from 4 to 10 in the morning and 5 to 8 in the evening. Not only do we eat pulses, but also any vegetable and food we want. Earlier, we could not imagine asking for leave even in health emergencies. Today, I can go anywhere I want. I have got wings,” smiles Chinnathambi.

Together, all these workers make and bake bricks in the kiln. “We purchase the bricks made by these workers to be used for constructing houses under the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana,” says the IAS officer, who has been in the service for the past decade. So far, the administration has bought around 1.8 lakh bricks from them.

Prevention, protection, rehabilitation

In a bid to eradicate bonded labour, the district administration has directed brick kiln associations to hoard a banner at every working site. A banner stating the number of workers employed at the site, their wage details, and other particulars has been hoarded in each and every 252 brick kilns in the district, says the IAS officer. The administration has also put out a helpline number [18005997696] for getting information about bonded labour in any place.

“We have set up multi-disciplinary inspection teams to inspect for any labour-related violations in the district. We have also directed the proprietors to issue formal appointment letters to the brick kiln workers. Earlier, it was a completely informal relationship between the employer and the employee, which forced them into slavery,” Verghese says.

The IAS officer says his approach is ‘Prevention, Protection, and Rehabilitation’, through which the district has been able to sustain the project. “We are working on these three pillars to provide a life of dignity to these workers. We have been taking a lot of actions, from creating awareness and training them to switch to alternate livelihood options,” he says.

“These workers have been rehabilitated to not only work at their own brick kiln but also to earn an alternative income. We assist and train them in selling embroidery work, and provide communities with fishnets, sewing machines, etc. We are now setting up poultry farms to boost their income.”

So far, nearly Rs 30 lakh from various schemes, including the State Rural Livelihood Mission and MGNREGA, have been utilised for the purpose, Verghese adds. “Historically, we have been known to have the issue of bonded labour, but we have been able to reduce that in our district to a certain extent. It is still prevalent, but we are taking efforts to eradicate it completely.”

“I keep getting requests from more workers for rehabilitation. It would be incorrect to say that every problem has been addressed because if we do, we will stop looking for grievances. It is a continuous process, but it is satisfying to see how these many workers are self-empowered now.”